TREES

(eight of them)

ON THE WAY TO MY CAR

AFTER THE FIELD TRIP

(and a year ago)

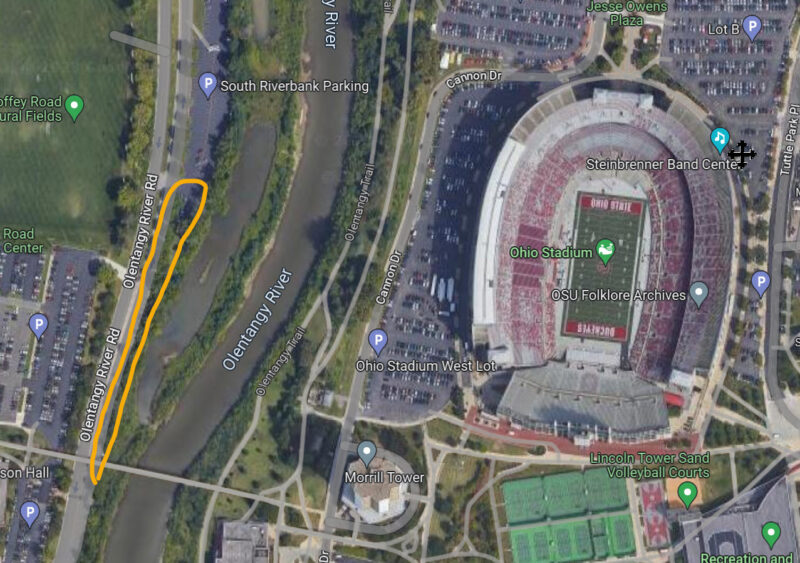

On the way back from Jennings after the trip to Batelle Darby Metro Park I suddenly remembered the tree assignment was due, so I got ’em all in the stretch of sidewalk along Olentangly River Road from the pedestrian bridge that crosses the river to the parking lot a few hundred yards north of it. The area is shown in the outlined portion of the image below. That was easy!

Tree walk.

There are trees there. Who knew? As Gabriel Popkin explained so well in her article (LINK), a lot of otherwise well-educated people are “tree blind.” I’m a botanist, so I guess I’m somewhat less tree blind than most folks, but still have a lot to learn, especially about oaks and hickories …and pines …and hawthorns, and…

white mulberry

(Morus alba)

White mulberry leaves are alternate in arrangement, simple in complexity, and with a margin that is coarsely toothed, and also varies from being entire to lobed, sometimes deeply so.

White mulberry leaves vary in the degree to which theyu are lobed.

There are several small trees growing between the sidewalk and the Olentangy River.

White mulberry is a roadside tree.

Mulberries are doiecious, i.e., with separate male and female individuals. It was flowering about a week ago, when I took these pictures of late-stage flowers. The males are in short catkins.

Mulberry male flowers.

Originally from Asia, Petrides (1958) tells us that white mulberry was brought here by the British prior to the American Revolution in an unsuccessful attempt to establish a silkworm industry.

Like raspberries and blackberries, mulberries are gtoups of many small fruits. Unlike those members of the rose family which are aggregate fruits, i.e., derived from a single flower with an apocarpous gynoecium, mulberries are multiples originating from head-like compact inflorescences. But what type of fruits are they multiples of? I had always assumed that, like blackberries and raspberries, that they were drupes. Nope! According to H.A. Gleason in “The New Britton and Brown Illustrated Flora of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada” (1968) tells us that the fruit is “…a short-cylindric syncarp resembling a blackberry, composed of the juicy, accrescent but not coherent calyces, each enclosing a small seed-like achene, with the remains of the styles protruding.” Hmm. Juicy calyces enclosing achenes, wow! Below see a closeup taken June 1, 2023. You can see that the juicy parts are separable.

The mulberry is a multiple of achenes each surrounded by juicy calyces.

Common buckthorn

(Rhamnus cathartica)

Common buckthorn leaveds are sub-opposite.

Buckthorn is an undesirable non-native tree with oblong. serrate sub-opposite leaves. Introduced as a hedgerow plant in the early years of European settlement of North America, it has spread into natural areas, especially in calcareous soils. The cathartic nature of the fruits (purple-black berries produced abundantly all along the stems) enhances their rapid dispersal by birds.

The tips of buckthorn twigs end in a thorn-like point.

Red elm

(Ulmus rubra)

Elm (genus Ulmus) have leaves that are simple in complexity, with a doubly-serrate margin, and a peculiarly unequal-sided leaf base. There are two common species in Ohio –American elm (U. americana) and red/slippery elm, U. rubra. They are quite similar. Red elm leaves are more scratchy above than are those of American elm, and there are also some differences in the bark and the fruits.

Elm leaves are doubly-toothede, and unequal-sided at the bases.

In North America, elm tree populations are a mere remnant of what they once were. As explained very well by the Morton Arboretum, the disease –which is probably of Asiatic, not Dutch, origin was accidentally introduced to the U.S. in the 1930’s. It is a fungus that is carried by two species of bark beetles. All of our native elms are susceptible. The fungus blocks the water-carrying xylem tissue, causing affected branches to wilt and die. Because elms reproduce at an early age, there are still elms around, just not many forest giants like there once were. In her “tree blindness” article, Popkin mentions several other introduced tree pathogens, citing primarily the emerald ash borer as a consequence of global trade, whicj is noted to be “only the latest iteration of this sad story; chestnuts, hemlocks and elms have already taken major hits from foreign pests.”

Hackberry

(Celtis occidentalis)

Hackberry is a member of the elm family (Ulmaceae) and shares with elms the overall leaf appearance –simple, alternate, doubly-serrate, and with an unequal-sided leaf base.

Hackberry leaves are selm-like but singly and coarsely toothed.

Just based on the leaves, hackberry is a pretty indistinctive tree. It looks vaguely elm-like. In fruit, it stands apart from elms by bearing little pea-sized drupes, very unlike the dry flat winged samaras of elms. Hackberry bark is more deeply furrowed than any other Ohio tree. Later in the season look for little pencil-eraser shaped projections on the bottoms of hackberry leaves that are galls caused by a psyllid (a type of true bug in the order hemiptera). According to the Texas A&M extension service, these litle bugs sometimes enter homes!

Redbud

(Cercis canadensis)

This is the tree the artists and editors of the New York Times used to illustrate their “Tree Blindness” article. A good choice, as it is striking in many respect and I imagine it is indeed a great thrill to watch as “pollen-drunk” bumblebees forage on the flowers.

Redbud looks like little Valentine hearts. Aww!

the other iphone photos aren’t so great

so here’s are 3 trees from the same area last year

A parking lot that practically an arboretum!

American sycamore

(Platanus occidentalis)

American sycamore is also a lowland tree, occurring mainly along rivers, ut it also does well as a street tree, perhaps because of similar stresses, namely low oxygen concentration in the soil around the root system.

A large sycamore by the river and by the road.

Sycamore can get very big! In “Flora of West Virginia,” P. D. Strausbaugh and Earl L.Core mention some pioneers named John and Samuel Pringle who lived in a hollow sycamore tree near the present site of Buckhannon (Upshur County WV) from 1764 to 1768. Sounds like fun, but it could get old after a while. (“I am so sick of this sycamore!”)

The bark is distinctive, with pieces sloughing off in irregular jigsaw-puzzle like pieces. Eventually it become quite white (in very old specimens).

Sycamopre bark looks like a jigsaw puzzle!

The leaves are alternate in arrangement, simple in complexity, and palmately lobed. (Were it not for the non-opposite leaf arrangement, one could mistake this for a maple.)

American sycamore looks somewhat maple-ish,don’t you think?

American sycamore is sometimes called “buttonwood” A web site called “Dave’s Garden” (LINK) has an explanation, saying the name is self-explanatory as it was a favorite wood for making buttons. Dave also tells us that the New York Stock Exchange was founded in 1792 according to a pact made beneath a sycamore growing along Wall Street, henceforth called the “Buttonwood Agreement.”

Eastern Cottonwood

(Populus deltoides)

At Waterman Agricultural and Natural Resources Laboratory on Kinney Road (better known as “Waterman Farms”), a drainage ditch meanders across the tract. Low-lying soil is home to eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides).

This is a fast-growing lowland species, in the same genus (Populus) as aspen. Here’s a tree joke: Question: Why do places like Indonesia, India and China have so many aspen and cottonwood trees? Answer: Because those are very Populus places!

Eastern cottonwood leaves are distinctively triangular. The specific epithet “deltoides” in in reference to the leaf shape.

Eastern cottonwood has deltoid (triangular) leaves.

Aspen and cottonwood leaves tremble in the slightest breeze because they have flattened petioles. (I call them “linguine leafstalks.”)

Linguine leafstalks!

Ohio Buckeye

(Aesculus glabra)

Ohio buckeye is a distinctive small tree, owing to its large, oppositely arranged palmately compound leaves. There are many of them growing along the Olentangy River Road parking lot.

Ohio Buckeye leafs out very early.

As explained so well by Joe Boggs, writing for OSU Agricultural Extension HERE (link) an odd syndrome of drooping laves is caused by the presence of the larvae of a small native moth called the Buckeye Petiole Borer (Proteoteras aesculana). Eggs are laid on the leafstalk and a caterpillar bores into it, where it devours some of the contents, cutting off circulation to the leaf, which eventually dies and drops to the ground.