MARSH, PRAIRIE AND FEN

Our first stop was a prairie-like wetland along Darby Creek Drive. This area was wisely purchased by Franklin County Metro Parks while it was farmland. It sits within the watershed of Big Darby Creek, a State and National Scenic River. This is a pristine watercourse known for its richness in fish and mussel diversity. Both to help protect the creek from run-off and create wildlife habitat on-site, the Parks people in 2010 restored natural hydrology by breaking drain tiles, and planted prairie grasses. It is now a magnificent wetland,

The wetland is dominated by “graminoids,” i.e., herbaceous plants in the grass or sedge families, which are characterized by having long linear leaves and reduced wind-pollinated flowers. One of the graminoids is a sedge called “wool grass” (decidedly not a grass however), Scirpus cyperinus, distinguished by having a big bushy panicle of small spikelets. The fruiting plants have their achenes surrounded by long hair-like bristles that gives them a woolly aspect this time of year.

Scirpus cyperinus is “wool grass.”

Some woody plants are beginning to colonize the wetland, including representatives of two genera in the willow family (Salicaceae). Eastern cottonwood, Populus deltoides is the most widespread of these.

Eastern cottonwood has triangular leaves and a flattened leafstalk (petiole).

Another wetland woody is willow, genus Salix, distingusihed by having long narrow leaves. Most of our willows are shrubs, not trees. This I believe is black willow, Saliz nigra, a tree willow common along watercourses.

Black willow, Salix nigra is a tree with narrow leaves.

Willow has an interesting history as a medicinal plant. Ancient people in several parts of the world have used willow bark, sometimes administered by chewing twigs or a s an infusion (tea) as pain relief. The active ingredient, salicin, is the same as in aspirin, the technical name for which is acetylsalicylic acid –note the reference to the genus Salix in the chemical name!

From there we went to a prairie at the Indian Ridge section of the park. Although this region is within an area where, in pre-settlement time, there were scattered and in some places extensive areas of prairie, this site is not a natural remnant but rather a “restored” (planted) prairie. This is an example of a tallgrass prairie, dominated by, well, tall grasses, prominent among which is big blueatem, Andropogon gerardii. This grass is easily recognized by its clusters of a few one-sided spikes of spikelets that give it another common name, “turkey-foot.”

Big bluestem, Andropogon gerardii, is a signature plant of the tallgrass prairie.

Other grasses that are abundant here are Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans) and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum).

Prairie forbs (i.e., herbaceous plants that are not grass-like) are well represented by members of the aster and legume families, most of which were done blooming when we were there. The most conspicuous wildflower today is stiff goldenrod, Solidago rigida.

\Stiff goldenrod is an abundant and showy forb.

An hour later, we were at Cedar Bog (that isn’t a bog) in Champaign County. While we were there we kept our eyes open for plants that, according to Jane Forsyth in her brand-new forty-seven year old article “Linking Botany and Geology –a New Approach (The Explorer 1971), are limited to limestone or limey sites.

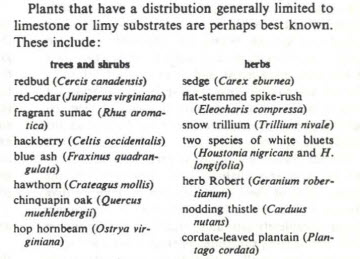

Plants of limestone areas, from the Jane Forsyth “Geobotany” article

We did see couple of these: hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) and chinquapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii). Here’s the oak. Note that is it a member of the white oak group, as the leaves have rounded, not bristle-tipped lobes, and so shallowly lobed that they might be better considered serrate.

Chinquapin oak is a characteristic tree of calcareous sites.

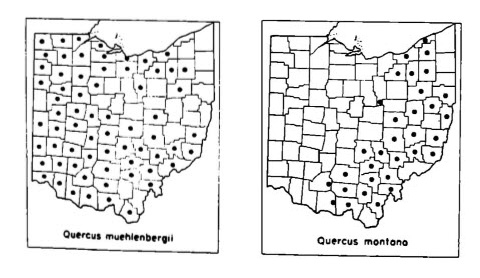

In the classic work “Woody Plants of Ohio” (1961) E. Lucy Braun presents a range map for chinquapin oak that seems to show it more widely ranging across Ohio than you would expect for a tree that is a pronounced calciphile. However, in the text she notes (p. 123) “…most common on the limestone soils of southwestern Ohio, a fact the distribution map does not show.” Below see the distribution maps of this species and a similar-appearing ine with a sharply different substrate affinity, rock chestnit oak, Quercus montata, a species we will be on our Hocking Hills trip.

Distribution maps for two members of the white oak group in Ohio

frm E. Lucy Braun (1961) The Woody Plants of Ohio (OSU Press)

Before entering the bog that isn’t a bog we were given an introductory presentation by the director there, Mike Kracken, who explained the difference between a bog and a fen, and why Cedar Bog is actually Cedar Fen! Bogs clog and fens flush…which is to say that fens are fed from underground springs that percolate up through the sediment which is rich in calcium minerals that become dissolved in the water. The spring were formed when glacial-transported gravel filled the valley of an ancient river system, the Teays (proniunced taze) River. The water is cool, which effectively shortens the growing season. Mike explained that Cedar Bog (which isn’t a bog) is unique in that plants from three different phytogeographic affinities are found in this one spot: northern bog plants, prairie plants and mid-western fen plants.

Cedar Bog open fen meadow. Note the northern white-cedar trees on the right.

In addition to the eponymous Thuja (cedar) trees that were abundant, we saw a couple of unusual woody plants you are unlikely to see unless you are at a special natural area like this. Look but don’t touch, it’s poison-sumac, Toxicodendron vernix! This close relative of poison-ivy has the same allergenic component –a non-volative oil called urushiol, but its slightly different chemical form (something to do with side chains as mentioned in this Wikipedia entry) this species causes a more severe dermatitis. Yikes!

Poison sumac is a rare plant found in high-quality wetlands.

Poison-sumac is distinctive, if you look at the combination of characters, including the specialized bog or fen habitat. It has alternate pinnately compound leaves with entire (not toothed as in the “friendly” sumacs, i.e. smooth, staghorn, winged and fragrant (all in the genus Rhus), that are fairly large. In fruit, there are drooping racemes of white drupes. (Note the the aforementioned friendly sumacs all have red drupes.)

Another specialty of swamps is black ash, Fraxinus nigra. Ashes are annoyingly similar to one another, and to make matters even more confusing, all of our ashes have common names that are colors’ there’s black ash (Fraxinus nigra), white ash (F. americana), blue ash (F. quadrangulata), red ash (F. pennsylvanica), green ash (also F. pennsylvanica) and pumpkin ash (F. profunda). Wondering about pumpkin ash fitting into the name = color rule? It’s simple. A pumpkin is an orange fruit, and the other prominent fruit that is orange is called an “orange.” So therefore, the name of any fruit that reflects light in the ~ 635–590 nm wavelength range can officially serve as the word for that color. This must be true because I read it on the internet (never mind that I only just wrote it on the internet myself). Let’s celebrate! It’s Nationals Circuitous Logic Day!

Black ash has sessile (non-stalked) leaflets.

To recognize this unusual ash, look for more a few more leaflets than you usually see on ashes, and note how they are attached to the rachis (leafstalk): they are sessile (non-stalked), in contrast to the stalked leaflets of our other ashes.

There are a number of specialized herbs at Cedar Bog that isn’t a Bog. Among them is a thistle that looks a bit like the nasty evil invasive canada thistle but is actually a prized wildflower found in only a few places in Ohio: swmap thistle, Cirsium muticum is identified by its phyllaries (involucral bract) that are gummy-sticky instead of being sharp-pointed in other thistles (including some other very valued wildflowers such as pasture thistle).

Swamp thistle is an uncommon wildflower in the Aster family.

Ha! I like flowers that resemble things and are named for those whimsical resemblances. Turtlehead, Chelone glabra is a wetland perennial in the Plantaginaceae (formerly in the Scrophulariaceae) that has flowers that look that way I guess.

Turtlehead!

We saw some bryophytes, including a huge thallose liverwort, Conicephalum (the specific name of this plant is uncertain at present). It is growing on the ground in the wooded swampy part of the preserve.

Conocephalum is a large thallose liverwort.

Closeup, note the textures appearance of this liverwort, looking (or so it is said) rather snakeskin-like.

Conocephalum is camplex thallose liverwort.

Rare goldenrods! With their small capitula of bright yellow flowers arranged in a variety of compound inflorescence, goldenrods brighten the late-summer landscape. While several species, such as the ubiquitous Canada goldenrod, with a Coefficient of Conservatism of 1, are widespread along roadsides and meadows across the state, some are highly restricted to special habitats. Two such highly conservative (CC=9 for both) members of the genus Solidago are Ohio goldenrod (S. ohioensis) and bog goldenrod (S. uliginosa). Both are delicate, and each is fairly distinctive. Ohio goldenrod is flat-topped.

Ohio goldenrod is a flat-topped rarity of fens.

Bog goldenrod, Solidage uliginosa is wand-like.

Bog goldenrod, Solidago uliginosa, is a wand-shaped rarity of fens and bogs.

Oh hip-hip-hooray! We finally got to see a flowering member of one of our “big eight” plant families, the Rosaceae. This is shrubby cinquefoil, Dasiphora (formerly Potentilla) fruticosa, a shrubby yellow-flowered plant that is actually common in cultivation. Note the rose family traits of regular (radially symmetric) flowers with 5 separate petals, many stamens and many carpels, spirally inserted. Too bad the photo doesn’t show the stipules on the leaves.

Shrubby cinquefoil, common outside fast-food restaurants but rare in nature (at least in Ohio).

There’s a wildflower here called “grass of Parnassus” that is definitely not a grass.

Grass-of-Parnassus bears a solitary flower on a long scape.

The flowers of grass-of-parnassus flowers have five deeply 3-lobed nectariferous staminodes alternating with the pollen-producing stamens.

Details of Parnassia flower.

Many other unique plants grow here. Since the nutrient levels are quite low, and the growing season short, some of them supplement their nutrient supply by digesting small animals. Carnivorous plants!!

One obviously carnivorous plant is the round-leaved sundew, Drosera rotundifolia. Its leaves are beset with sticky-tipped hairs that insects or other arthropods get stuck to like flypaper.

Sundews are carnivorous. The leaves are sticky.

Photo taken in May 2018

Less obvious, unless you were to go pulling them out of the bog that isn’t a bog (It’s a fen!) are the bladderworts. These have leaves that are underwater, much divided, and some of the leaflets are modified into little pitchers that suck in tiny invertebrates that inadvertently touch trigger hairs in these bladders. The flowers are normal-looking, resembling yellow snapdragons.

Bladderwort plants capture tiny invertebrates with underwater bladders at the ends of their leaves.

Photo taken in May 2018

Deep Woods Farm (Hocking Hills Region)

This is a private nature preserve in Hocking County. The Hocking Hills is in the unglaciated portion of Ohio, where the substrate is acidic sandstone. Dr. Forsyth listed plants associated with this bedrock type in her article.

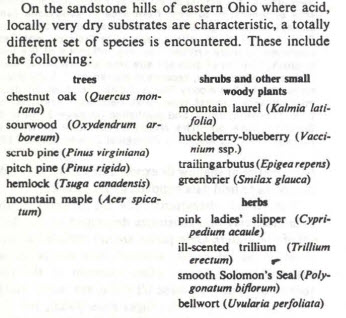

Plants of acid-soil sites, from the Jane Forsyth “Geobotany” article

We were able to observe several of these on the trip there: chestnut oak, sourwood, and hemlock. Here’s chestnut oak.

Cestnut oak. Quercus montana, is an acid-loving member of the white oak group.

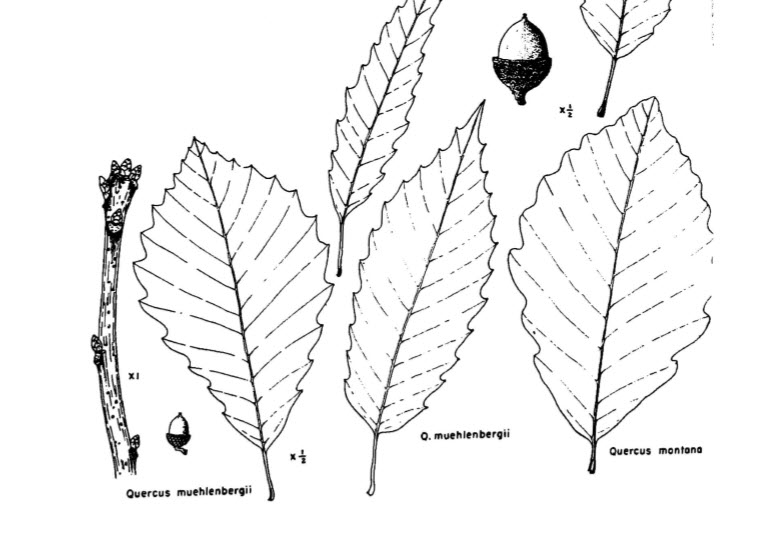

As is illustrated so well in E. Lucy Braun’s “Wood Plants of Ohio,” chestnut oaks serrations are round-tipped as compared to those of chinquapin oak.

Two similar white oaks with different geological substrate affinities.

from E. Lucy Braun (1961) The Woody Plants of Ohio (OSU Press)

We started the foray on a shallow-soil glade-like ledge that was home to a bed of mosses and lichens. particularly Polytrichum ohioense (not shown) and “dixie reindeer lichen,” Cladonia subtenuis. The reindeer lichens are have a tangled growth form that is quite distinctive. This species is a yellowish color, and predominantly whorled branches. I didn’t notice it at the time, but the photo shows apothecia (spore-producing regions) at the tips of the branches. That is an uncommon sight!

Cladonia subtenuis is a reindeer lichen.

The ledge is an area of low nutrients, so is is not surprising to see members of the pea family, Fabaceae, as they are capable through the actions of bacteria in their roots, to “fix” (acquire) atmospheric nitrogen. This wildflower, especially welcome at a time when there are few others in bloom and nearly all of them are asters, is creeping lespedeza, Lespedeza procumbens.

Creeping lespedeza is a low-growing member of the pea family.

Moss is boss! A deep cool moist recess in a sandstone ledge is home to the globally rare “sword moss,” Bryoxiphium norvegicum. It is one of the few mosses that are actually flat –with leaves in two opposite rows. Here it is seen with another, more common, genus of flat moss, Fissidens.

Sword moss, Fissidens, and a little tuft of Atrichum photo-bombing.

photo taken May 2017

Another brophyte, not quite as rare as the swod moss, is the less common of two fairly common Plagiomnium mosses (some others are rare). This is Plagiomnium ciliare. Unlike the ridiculously common P. cuspidatum, the leaves of which are toothed only halfway down the margin, this one is toothed all the way.

The less common of two fairly common Plagiomnium mosses.

An exciting, albeit somewhat depressing sight was this iconic American chestnut. This species, Castanea dentata, was once a major component of forests in much of the eastern U.S., but nearly all the trees were killed by an Asian fungus during the 1st half of the 20th century. Chestnut persists as stump sprouts. When the trees get about pole-sized, the fungus, which infects the bark, kills the tree. In the photo below, you can see the dead trunk of the previous sprout.

American chestnut regenerating from stump-sprouts.

American chestnut is a member of the beech family (Fagaceae), and its leaves are somewhat beech-like. Oaks are also a member of the Fagaceae.

American chestnut leaves are similar to those of American beach, but larger and more pointed.