INTRODUCTION TO FIELD TRIPS

OHIO GEOBOTANY

Ohio Plants explores natural areas in two markedly dissimilar regions of Ohio, and interprets them based on the analysis of geology and vegetation set forth in noted Ohio geologist Jane Forsyth’s 1972 article ““Geobotany: Linking Geology and Botany.” In is, she tells us that the Geology of Ohio is divided into two parts.

WESTERN OHIO: underlain by erodible limestone and dolomite.

The result after 200 million years of erosion is flat level landscape.

EASTERN OHIO: underlain by erodible shale capped by erosion-resistant sandstone.

There result after erosion is deep valleys of steep-sided sandstone hills.

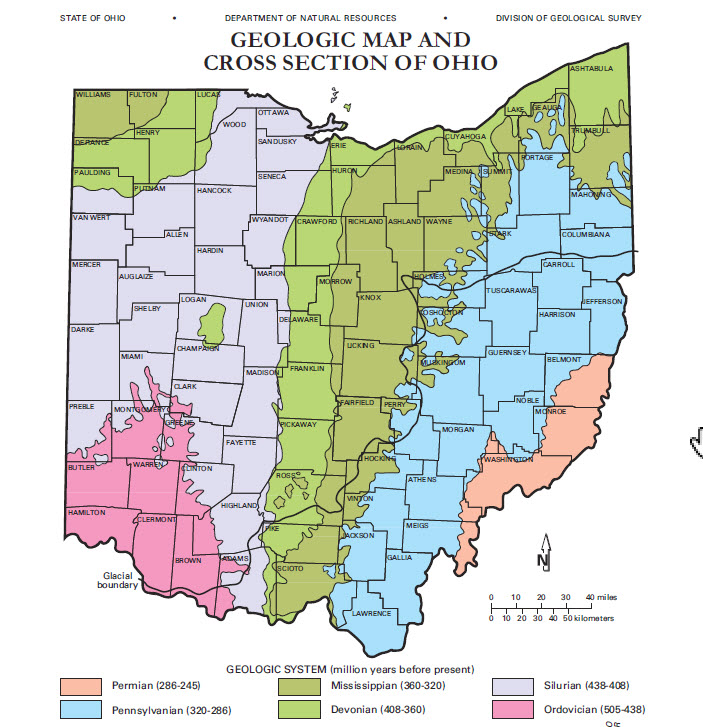

Geologic Map of Ohio

This has resulted in there being very different substrates for plants in the two parts of Ohio.

WESTERN OHIO

Here the soil is limey clay glacial till, impermeable, high in nutrients. Some spots without till are thin dry limestone. A plant associated with this geological history is blue ash, Fraxinus quadrangulata.

Blue ash is found in high pH areas.

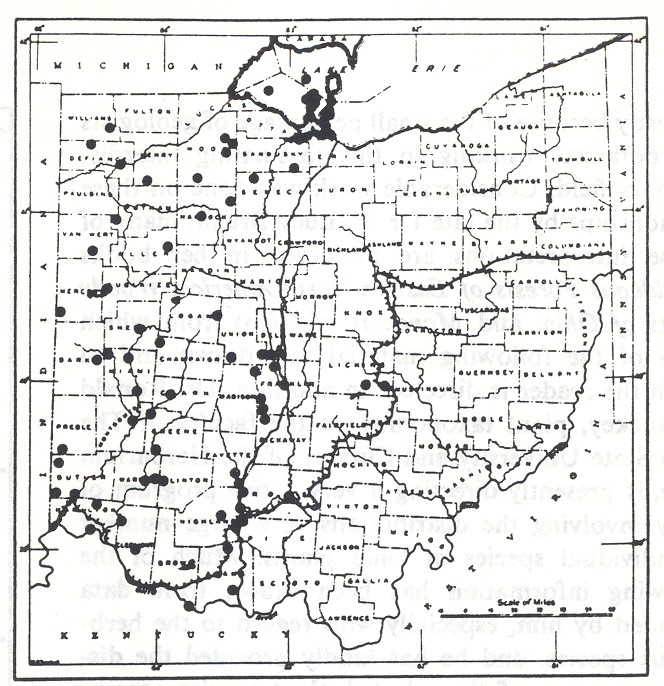

Map prepared by Ronald Stuckey, and included in Forsyth’s “Geobotany” article.

EASTERN OHIO

Here the soil is built from permeable sandstone bedrock, very acidic, low in nutrients. A plant associated with this soil makeup is chestnut oak, Quercus montana.

Chestnut oak is found in low pH areas.

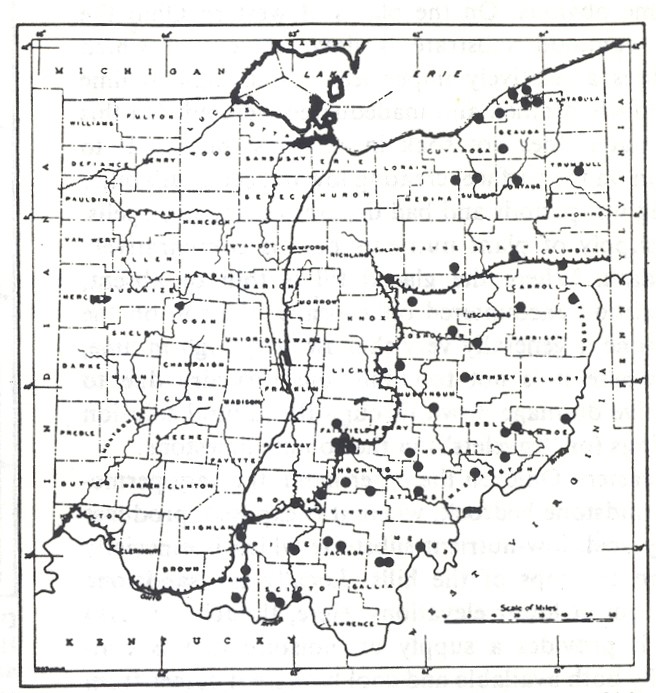

Map prepared by Ronald Stuckey, and included in Forsyth’s “Geobotany” article.

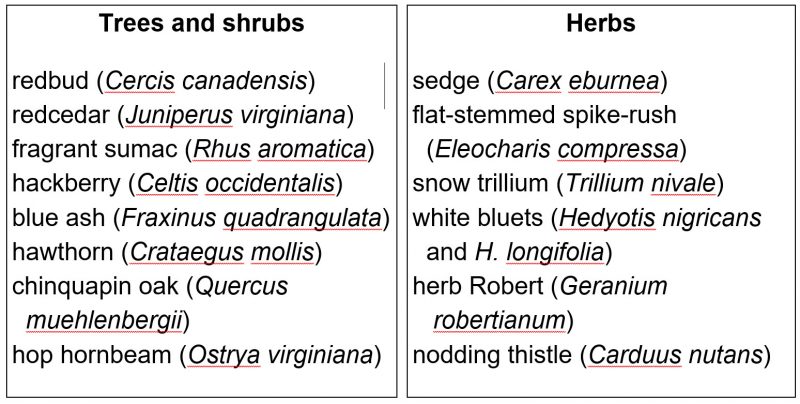

A whole host of plants are associated with limey soils and exposed limestone bedrock.

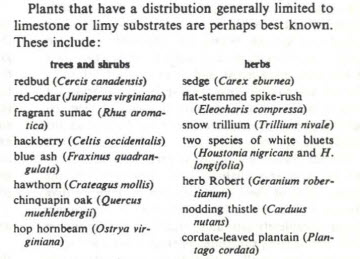

PLANTS WITH A DISTRIBUTION GENERALLY LIMITED TO LIMESTONE

Earlier this year I put together an Ohio Geobotany exhibit for the Museum of Biological Diversity Open House, and made this set of table based on Forsyth’s article. It fits in here too (hooray for recycling).

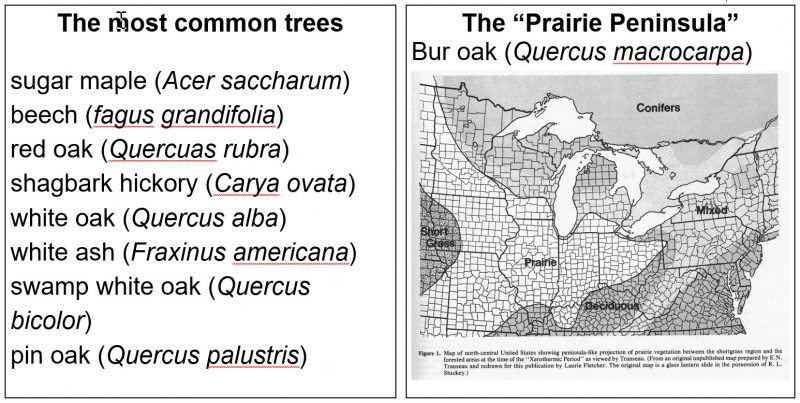

The characteristic plants of the more fertile and deeper soils found across the great till plains covering more than half the state are many majestic forest trees.

TREES OF THE HIGH-LIME CLAY-RICH TILL OF THE WESTERN OHIO PLAINS

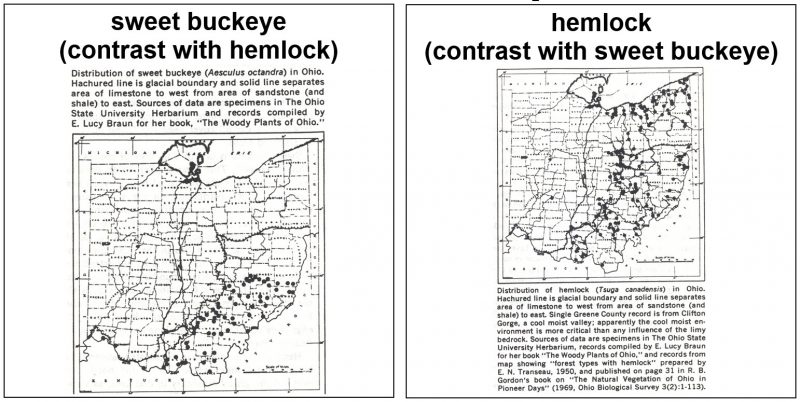

PLANTS OF ACID DRY SANDSTONE HILLS OF EASTERN OHIO

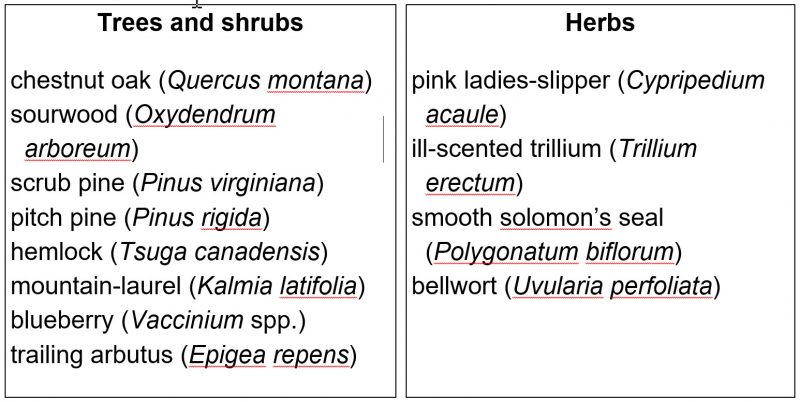

Noting the sharp differences in landscape and soil chemistry between glaciated and unglaciated portions of Ohio, Dr. Forsyth turned to Dr. Stuckey’s maps to ascertain what forces control the distribution of regionally restricted plants.

What is the major determinant of the distribution of these species?

Good question! Both are found principally south of the glacial bounary, and both have an affinity for acid soils, but note the difference: the coniferous tree eastern hemlock currently occurs on sites that were ice-covered during the last glacial advance, but the sweet buckeye stayed in place. Forsyth suggests that the cool moist ravines in northeast Ohio constitute favorable conditions for hemlock, and its wind-dispersed seeds enable rapid geographic spread. Buckeye, on the other hand, may simply not have had the dispersal ability to re-colonize the land exposed after the glaciers’ retreat.

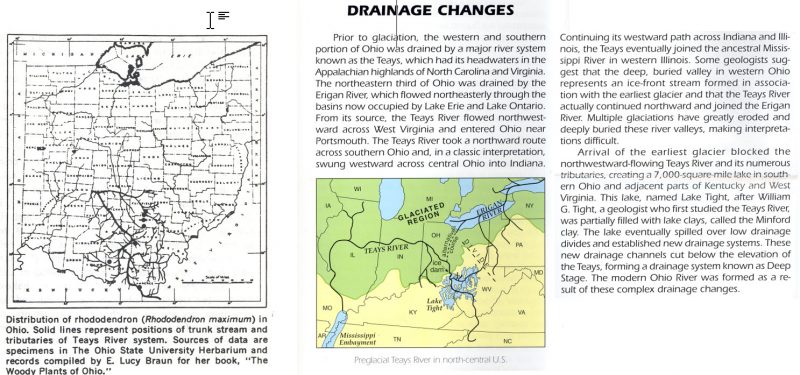

Plants of the ancient Teays River drainage

MARSH, PRAIRIE AND FEN

Our first stop was a prairie-like wetland along Darby Creek Drive. This area was wisely purchased by Franklin County Metro Parks while it was farmland. It sits within the watershed of Big Darby Creek, a State and National Scenic River. This is a pristine watercourse known for its richness in fish and mussel diversity. Both to help protect the creek from run-off and create wildlife habitat on-site, the Parks people in 2010 restored natural hydrology by breaking drain tiles, and planted prairie grasses. It is now a magnificent wetland.

Marsh at Batelle Darby MetroPark.

The wetland is dominated by “graminoids,” i.e., herbaceous plants in the grass or sedge families, which are characterized by having long linear leaves and reduced wind-pollinated flowers. One of the graminoids is a Torrey’s rush, Juncus torreyii. It’s an especially robust rush, with globose heads of small flowers.

Rushes are graminoids with small flowers that resemble miniature lilies.

Some woody plants are beginning to colonize the wetland, including representatives of two genera in the willow family (Salicaceae). Eastern cottonwood, Populus deltoides is the most widespread of these.

Eastern cottonwood has linguine leafstalks!

Another wetland woody is willow, genus Salix, distingusihed by having long narrow leaves. Most of our willows are shrubs, not trees. I forgot to take a photo of it, but still enjoyed observing it.

Willow has an interesting history as a medicinal plant. Ancient people in several parts of the world have used willow bark, sometimes administered by chewing twigs or a s an infusion (tea) as pain relief. The active ingredient, salicin, is the same as in aspirin, the technical name for which is acetylsalicylic acid –note the reference to the genus Salix in the chemical name!

From there we went to a prairie at the Indian Ridge section of the park. Although this region is within an area where, in pre-settlement time, there were scattered and in some places extensive areas of prairie, this site is not a natural remnant but rather a “restored” (planted) prairie. This is an example of a tallgrass prairie, dominated by, well, tall grasses, prominent among which is big bluestem, Andropogon gerardii. This grass is easily recognized by its clusters of a few one-sided spikes of spikelets that give it another common name, “turkey-foot.”

Big bluestem is a signature grass of the tallgrass prairie.

Other grasses that are abundant here are Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans) and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum).

Prairie forbs (i.e., herbaceous plants that are not grass-like) are well represented by members of the aster and legume families, most of which were done blooming when we were there. The most conspicuous wildflower today is stiff goldenrod, Solidago rigida.

Stiff goldenrod is a prairie forb.

An hour later, we were at Cedar Bog (that isn’t a bog) in Champaign County. While we were there we kept our eyes open for plants that, according to Jane Forsyth in her brand-new forty-seven year old article “Linking Botany and Geology –a New Approach (The Explorer 1971), are limited to limestone or limey sites.

Plants of limestone areas, from the Jane Forsyth “Geobotany” article

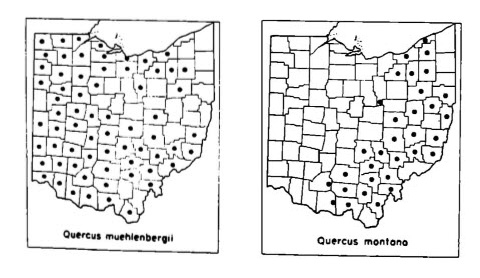

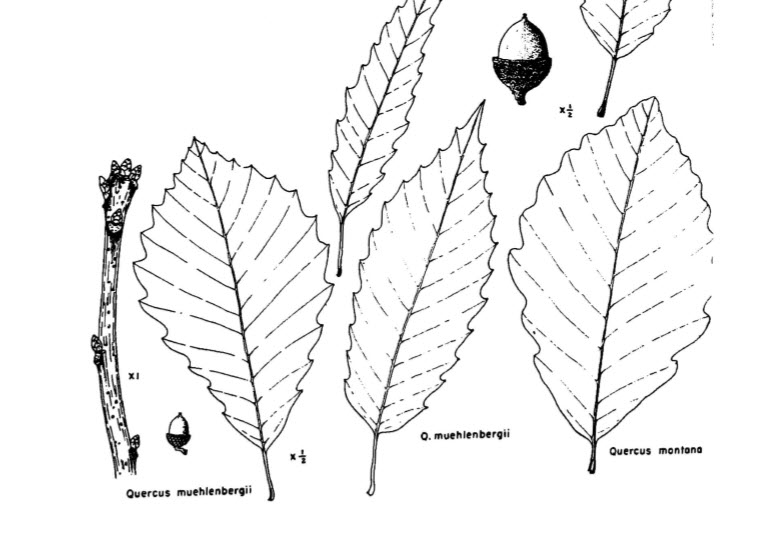

We did see couple of these: hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) and chinquapin oak (Quercus muehlenbergii). Here’s the oak. Note that is it a member of the white oak group, as the leaves have rounded, not bristle-tipped lobes, and so shallowly lobed that they might be better considered serrate.

Chinquapin oak is a member of the white oak group.

It resembles chestnut oak, but has sharper lobes.

In the classic work “Woody Plants of Ohio” (1961) E. Lucy Braun presents a range map for chinquapin oak that seems to show it more widely ranging across Ohio than you would expect for a tree that is a pronounced calciphile. However, in the text she notes (p. 123) “…most common on the limestone soils of southwestern Ohio, a fact the distribution map does not show.” Below see the distribution maps of this species and a similar-appearing ine with a sharply different substrate affinity, rock chestnit oak, Quercus montata, a species we will be on our Hocking Hills trip.

Distribution maps for two members of the white oak group in Ohio

frm E. Lucy Braun (1961) The Woody Plants of Ohio (OSU Press)

Before entering the bog that isn’t a bog we were given an introductory presentation by the director there, Mike Kracken, who explained the difference between a bog and a fen, and why Cedar Bog is actually Cedar Fen! Bogs clog and fens flush…which is to say that fens are fed from underground springs that percolate up through the sediment which is rich in calcium minerals that become dissolved in the water. The spring were formed when glacial-transported gravel filled the valley of an ancient river system, the Teays (proniunced taze) River. The water is cool, which effectively shortens the growing season. Mike explained that Cedar Bog (which isn’t a bog) is unique in that plants from three different phytogeographic affinities are found in this one spot: northern bog plants, prairie plants and mid-western fen plants.

Marl meadow at Cedar Bog that isn’t a bog.

In addition to the eponymous Thuja (cedar) trees that were abundant, we saw a couple of unusual woody plants you are unlikely to see unless you are at a special natural area like this. Look but don’t touch, it’s poison-sumac, Toxicodendron vernix! This close relative of poison-ivy has the same allergenic component –a non-volative oil called urushiol, but its slightly different chemical form (something to do with side chains as mentioned in this Wikipedia entry) this species causes a more severe dermatitis. Yikes!

Poison-sumac is a high quality wetland sgrub.

Just don’t touch it!!

Poison-sumac is distinctive, if you look at the combination of characters, including the specialized bog or fen habitat. It has alternate pinnately compound leaves with entire (not toothed as in the “friendly” sumacs, i.e. smooth, staghorn, winged and fragrant (all in the genus Rhus), that are fairly large. In fruit, there are drooping racemes of white drupes. (Note the the aforementioned friendly sumacs all have red drupes.)

Another specialty of swamps is black ash, Fraxinus nigra. Ashes are annoyingly similar to one another, and to make matters even more confusing, all of our ashes have common names that are colors’ there’s black ash (Fraxinus nigra), white ash (F. americana), blue ash (F. quadrangulata), red ash (F. pennsylvanica), green ash (also F. pennsylvanica) and pumpkin ash (F. profunda). Wondering about pumpkin ash fitting into the name = color rule? It’s simple. A pumpkin is an orange fruit, and the other prominent fruit that is orange is called an “orange.” So therefore, the name of any fruit that reflects light in the ~ 635–590 nm wavelength range can officially serve as the word for that color. This must be true because I read it on the internet (never mind that I only just wrote it on the internet myself). Let’s celebrate! It’s Nationals Circuitous Logic Day!

To recognize this unusual ash, look for more a few more leaflets than you usually see on ashes, and note how they are attached to the rachis (leafstalk): they are sessile (non-stalked), in contrast to the stalked leaflets of our other ashes.

Black ash is a swamp tree.

There are a number of specialized herbs at Cedar Bog that isn’t a Bog. Among them is a thistle that looks a bit like the nasty evil invasive canada thistle but is actually a prized wildflower found in only a few places in Ohio: swmap thistle, Cirsium muticum is identified by its phyllaries (involucral bract) that are gummy-sticky instead of being sharp-pointed in other thistles (including some other very valued wildflowers such as pasture thistle).

Swamp thistle has a sticky, not bristly, involucre.

Rare goldenrods! With their small capitula of bright yellow flowers arranged in a variety of compound inflorescence, goldenrods brighten the late-summer landscape. While several species, such as the ubiquitous Canada goldenrod, with a Coefficient of Conservatism of 1, are widespread along roadsides and meadows across the state, some are highly restricted to special habitats. Two such highly conservative (CC=9 for both) members of the genus Solidago are Ohio goldenrod (S. ohioensis) and bog goldenrod (S. uliginosa). Both are delicate, and each is fairly distinctive. Ohio goldenrod (not shown) is flat-topped, while bog goldenrod is wand-like.

Bog goldenrod is wand-like.

Oh hip-hip-hooray! We finally got to see a flowering member of one of our “big eight” plant families, the Rosaceae. This is shrubby cinquefoil, Dasiphora (formerly Potentilla) fruticosa, a shrubby yellow-flowered plant that is actually common in cultivation. Note the rose family traits of regular (radially symmetric) flowers with 5 separate petals, many stamens and many carpels, spirally inserted. Too bad the photo doesn’t show the stipules on the leaves.

Shrubby cinquefoil is a shrub in the rose family.

There’s a wildflower here called “grass of Parnassus” that is definitely not a grass. The flowers of grass-of-parnassus flowers have five deeply 3-lobed nectariferous staminodes alternating with the pollen-producing stamens.

Grass of Parnassus, definitely not a grass!

Oooh look, a syrphid (flower) fly! These bee-mimics can be important pollinators, as the avidly visit flowers. This one, according to my new “Field Guide to the Flower Flies if Northeastern North America” (Princeton Field Guides) appears to be Helophilus fasciatus.

A narrow-headed march fly, Helophilus fasciatus.

FIELD TRIP 1

Deep Woods Farm (Hocking Hills Region)

This is a private nature preserve in Hocking County. The Hocking Hills is in the unglaciated portion of Ohio, where the substrate is acidic sandstone. As shown above, Dr. Forsyth listed plants associated with this bedrock type in her article. We were able to observe several of these on the trip there: chestnut oak, sourwood, and hemlock. Here’s sourwood, Oxydendrum arboreum, a tree that is a member of the Ericacae, a markedly acid-loving family of mostly shrubs and herbs.

Sourwood is an acid-loving tree with leaves that taste pleasantly tart.

We saw the chestnut oak; I was too busy to snap a photo this year. It is illustrated so well in E. Lucy Braun’s “Wood Plants of Ohio” Chestnut oaks serrations are round-tipped as compared to those of chinquapin oak, a species we hope to see next week at Cedar Bog that isn’t a bog.

Two similar white oaks with different geological substrate affinities.

from E. Lucy Braun (1961) The Woody Plants of Ohio (OSU Press)

Another of the acidophiles that Forsyth mentions is an orchid, the pink lady’s-slipper, Cypripedium acaule. This plant flowered in late Spring, and now is maturing fruit. The fruit is a capsule filled with a great many dust-like seeds.

Lady’s-slipper orchid is setting fruit.

We started the foray on a shallow-soil glade-like ledge that was home to a bed of mosses and lichens. particularly “dixie reindeer lichen” (not shown) and Ohio haircap moss, Polytrichum ohioense.

Ohio haircp moss is a robust acrocarp of open sites.

The ledge is an area of low nutrients, so is is not surprising to see members of the pea family, Fabaceae, as they are capable through the actions of bacteria in their roots, to “fix” (acquire) atmospheric nitrogen. This wildflower, especially welcome at a time when there are few others in bloom and nearly all of them are asters, is creeping lespedeza, Lespedeza procumbens.

Creeping bush-clover is a member of the fabulous Fabaceae.

The ledge overtops a deep recess that we visited with a particular target in mind.

A deep recess where the Appalachian gametophyte thrives.

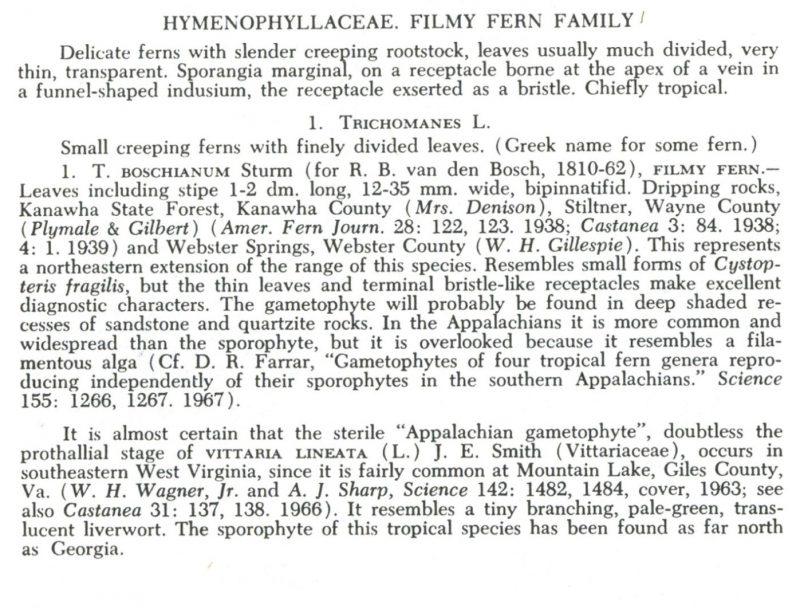

The Appalachian gametophyte is a fern that lost its sporophyte! A member of a tropical genus, Vittaria, this plant was once thought to represent the gametophye stage of a fern native to the southeastern U.S. Indeed, that was what

Doubtless?

The excerpt above is from “Flora of West Virginia,” by P. D. Strausbaugh and Earl L. Core. Flora of West Virginia was originally published in four parts, beginning with part one in 1952 and ending with part four in 1964. A group of six botanists from West Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina is updating the book for future publication. If I were hired to write the description of the Appalachian gametophyte for the new edition I would carefully read the 2016 American Journal of Botany article, “Unraveling the origin of the Appalachian gametophyte, Vittaria appalachiana” by Jerald B. Pinson and Eric Schuettpelz (American Journal of Botany).

Among fern species with long-lived gametophytes, perhaps none is as peculiar as Vittaria appalachiana. The “Appalachian Gametophyte” is one of only two ferns in our area that exist only as a gametophyte (the other one is weft fern, Crepidomanes intricatum, with an appearance much like a filamentous alga).

Appalachian gametophyte in cave at Deep Woods.

The Appalachian gametophyte resembles a thallose liverwort, being flat, translucent, and one cell thick. It doesn’t produce any gametangia, but reproduces only asexually by means of threadlike gemmae extending off of the margins. The gemmae are visible in the image above.

Pinson and Schuettpelz conducted a genetic analysis of Vittaria applachiana in which they discovered that it is not (as Strausbaugh and Core) the gametophyte of Vittaria lineata, but more closely related to a South American species, V. graminifolia. Because gemmae are so inefficient at long-distance dispersal, and the fact that the species is absent from previously glaciated regions of the northeastern U.S. where conditions seem suitable for it to grow (cool moist dark recesses in sandstone cliffs), the authors assert that the most likely explanation for its presence in the Appalachian region is not from dispersal from sothern sites where the fern carries out its entire life cycle. Rather, it seems to be a relic from pre-glacial times when conditions were more tropical and the fern thrived here. Cooling eliminated the ability for the fern to persist except in sheltered spots where the gametophye could persist, but only as an asexually reproducing entity.

Moss is boss! My special project at Deep Woods was to find and photograph several mosses. It was fun as usual to see the more well-lit walls of the natural bridge near the cave where the Appalachian gametophyte grows to be well occupied by cheerful rosettes of a distinctive cushion moss, Atrichum angustatum, recognizable by the longitudinal ribbons of tissue (lamellae) running along the leaf mid-nerve (costa).

Atrichum angustatum has lamellae on the costa!

Nearby, on an even sunnier but still damp ledge is an unusual moss that Natureserve Explorer calls “boar moss” (insert interobang here) ), but I’d prefer “cheerleader moss” for Brothera leana because the clusters of brood leaves in cute fluffy tufts are reminiscent of pom-poms.

Brothera leana should be called “cheerleader moss.”

Look, a turtle!

Look! A turtle!!