TREES

(eight of them)

I’m the GOAT!

I did it from a BOAT!

Today (Thursday September 1, 2022) I went to the Old and Dingy (ahem…) Olentangy River in the Clintonville area of Columbus, which I entered in my new foldable and very portable ORU Inlet Kayak! Would it be possible to observe and photo-document 8 trees from the water? Let’s find out.

On the water, facing north.

There are trees there. Who knew? As Gabriel Popkin explained so well in her article (LINK), a lot of otherwise well-educated people are “tree blind.” I’m a botanist, so I guess I’m somewhat less tree blind than most folks, but still have a lot to learn, especially about oaks and hickories …and pines …and hawthorns, and…

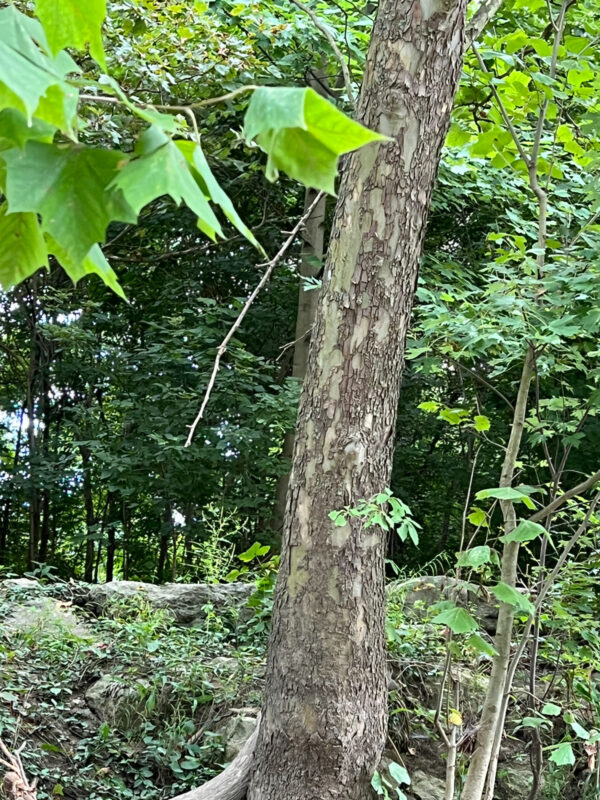

American sycamore

(Platanus occidentalis)

American sycamore is also a lowland tree, occurring mainly along rivers, but it also does well as a street tree, perhaps because of similar stresses, namely low oxygen concentration in the soil around the root system.

American sycamore along the river.

Sycamore can get very big! In “Flora of West Virginia,” P. D. Strausbaugh and Earl L.Core mention some pioneers named John and Samuel Pringle who lived in a hollow sycamore tree near the present site of Buckhannon (Upshur County WV) from 1764 to 1768. Sounds like fun, but it could get old after a while. (“I am so sick of this sycamore!”)

The leaves are alternate in arrangement, simple in complexity, and palmately lobed. (Were it not for the non-opposite leaf arrangement, one could mistake this for a maple.)

American sycamore leaves look somewhat maple-like.

American sycamore is sometimes called “buttonwood” A web site called “Dave’s Garden” (LINK) has an explanation, saying the name is self-explanatory as it was a favorite wood for making buttons. Dave also tells us that the New York Stock Exchange was founded in 1792 according to a pact made beneath a sycamore growing along Wall Street, henceforth called the “Buttonwood Agreement.”

Red elm

(Ulmus rubra)

Elm (genus Ulmus) have leaves that are simple in complexity, with a doubly-serrate margin, and a peculiarly unequal-sided leaf base. There are two common species in Ohio –American elm (U. americana) and red/slippery elm, U. rubra. They are quite similar. Red elm leaves are more scratchy above than are those of American elm, and there are also some differences in the bark and the fruits.

Red elm leaves are unequal-sided at the base.

In North America, elm tree populations are a mere remnant of what they once were. As explained very well by the Morton Arboretum, the disease –which is probably of Asiatic, not Dutch, origin was accidentally introduced to the U.S. in the 1930’s. It is a fungus that is carried by two species of bark beetles. All of our native elms are susceptible. The fungus blocks the water-carrying xylem tissue, causing affected branches to wilt and die. Because elms reproduce at an early age, there are still elms around, just not many forest giants like there once were. In her “tree blindness” article, Popkin mentions several other introduced tree pathogens, citing primarily the emerald ash borer as a consequence of global trade, whicj is noted to be “only the latest iteration of this sad story; chestnuts, hemlocks and elms have already taken major hits from foreign pests.”

Crack willow

Salix fragilis

Willows (genus Salix) comprise a large group of a few trees and a great many shrubs.

Willows are common streamside plants.

They generally have lance-linear leaves that are serrate and alternately arranged. The sexes are separate (dioecious). They typically grow in wet places. The identification of tis specimen as crack willow is based on the phenomenon whereby the branches are very brittle, snapping off with just the slightest pressure. When they fall onto wet soil, the root and establish new plants vegetatively.

Willows have narrow leaves.

George A. Petrides, in our “textbook” Peterson Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs mentions that willows are “most valuable in controlling streambank and mountainside erosion,” and that their bark provides a medicinal substance, salicin. This is a pain reliever chemically related to aspirin.

Green Ash

(Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

Green ash along the river.

Ashes are (except for the weird boxelder maple, sometimes thus called “ash-leaved maple”) our only trees with opposite pinnately compound leaves. Ash fruits are one-seeded achene-like affairs with a 2ing, called samaras, that are wind-dispersed. They resemble little canoe paddles.

Ash has opposite pinnately compound leaves and samara fruits.

Common buckthorn

(Rhamnus cathartica)

Buckthorn along the river.

Buckthorn is an undesirable non-native tree with oblong. serrate sub-opposite leaves. Introduced as a hedgerow plant in the early years of European settlement of North America, it has spread into natural areas, especially in calcareous soils. The cathartic nature of the fruits (purple-black berries produced abundantly all along the stems) enhances their rapid dispersal by birds.

Buckthorn leaves are almost but not quite opposite in arrangement.

The tips of buckthorn twigs end in a thorn-like point.

Twigs tips of buckthorn are pointed.

Honey-locust

(Gleditsia triacanthos)

Honey-locust along the river.

Honey-locust leaves are pinnately compound with rather small leaflets.

Honey-locust leaves have small leaflets.

Silver maple

(Acer saccharinum)

The “M” in “Madcaphorse (the memory hint for trees with opposite leaves), maples have opposite leaves. In our area all but one (boxelder maple) have simple leaves that are palmately lobed. This small shrub-like sapling was growing at the very edge of the pond, a testament to its typical wetland affinities.

Silver maple likes it wet.

Silver maple, along with red maple (Acer rubrum) is in the “soft maple” group, having softer wood than other maples, early maturing fruit, and leaves that are distinctly whitened beneath.

silver maple leaves are whitened beneath.

This is one of the trees we are trying hard to eliminate from the prairie. It is widespread, fast growing, and tenacious.

Mulberry leaves are coarsely serrate, with an outline that is variable. Some leaves are unlobed, others have a single large lobe, and a few have two or more lobes.

Mulberry leaves are the food for silkworm caterpillars, and it is for thatg reaso they were brought to the Americas during the colonial period, to establish a silkworm industry that ultimately proved unsuccessful.

White mulberry

(Morus alba)

Mulberry tree along the river

Mulberry leaves are coarsely serrate, with an outline that is variable. Some leaves are unlobed, others have a single large lobe, and a few have two or more lobes.

Mulberry leaves are the food for silkworm caterpillars, and it is for thatg reaso they were brought to the Americas during the colonial period, to establish a silkworm industry that ultimately proved unsuccessful.

Mulberry leaves are simple and serrate.

Northern catalpa

(Catalpa speciosa)

Catalpa is common along the Olentangy River.

The exciting thing about catalpa is the whorled leaves!

Whorled leaves!

Catalpa is sometimes called “cigar-tree” because of the long capsules that are produced abundantly.

Catalpa produces long narrow capsules,