THE “RESILIENCE TRACT”

Hocking County Ohio

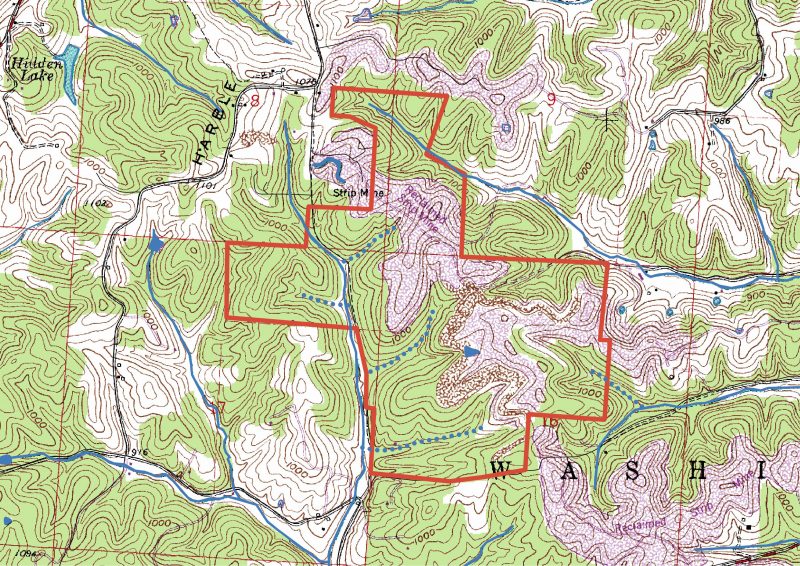

Midsummer I received an invitation to participate in a “bio-blitz” at a a 513-acre tract for which the a terrific land trust conservation organization, Arc of Appalachia, is seeking Clean Ohio funds for its purchase. It was explained that, to be able to buy this relatively large tract, AoA would need to rank highest among whatever other applications there were for funding this time around. Presently the land is privately owned. Rumor has it that just the timber alone would be worth about a million dollars! Below see a portion of an old-style 7.5 minute USGS quadrangle map with the property outlined.

Here’s what the area looks like on Google Maps.

A large portion of the area is forested. A ravine has a stream at its base, likely fed in part by acid coal mine drainage from the ridgetop above.

Wooded portion of Resilience Tract

The remaining acres consist of a reclaimed strip mine that covers the central ridgetop of the tract (probably mined in the 1980’s). Here’s a “time warp” video walking though a portion of the forest, across the meadow, and ending up at an open Virginia Pine stand.

The meadow, while in vegetation terms ranks very low on the FQAI scale as it is occupied almost entirely by non-native grasses and forbs, is nonetheless spectacular for its bird populations. Uncommon grassland birds are abundant here: Henslow’s Sparrow, Prairie Warbler, and Eastern Meadowlark.

Meadow on reclaimed surface mining site that is home to terrific grassland birds.

Some pernicious invasive plants are present in the meadow. Autumn-olive, Eleagnus umbellata, according s explained by Celastine Duncan on the TechLine Invasive Plant News web site o this web site, both Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) were introduced for what seemed like good reasons — landscaping, soil erosion prevention, and as food for wildlife. The site shows range maps and ID tips to separate the species, showing that the broader-leaved autumn-olive is the species more common in the eastern U.S., and the one we have here. Look for the distinctive Eleagnaceae family trait, the twigs and leaves are covered with round scales.

This plant is one of the few non-Fabaceae plants to carry out nitrogen-fixation, which is one oif the reasons it was extensively planted on reclamation sites. In a study published in Ecosphere in 2017, Elizabeth Malinich,Nicole Lynn-Bell,Peter S. Kourteve demonstrated that the shrub has effects oil microbial communities that depend depends on proximity of soils to plants

Autumn-olive

Eleagnus umbellata

Another nasty nitrogen-fixing shrub is taxonomically where you would expect it –in the fabulous Fabaceae. This is Chinese lespedeza, Lespedeza cuneata. The National Park Service, in their Plant Invaders of Mid-Atlantic Natural Areas web site, explain that this shrub was deliberately introduced for the same reasons as was autumn-olive.

Chinese lespedeza

Lespedesa cuneata

Despite the disturbed nature of the site, many lovely native wildflowers and shrubs are thriving here. Two are in the Hypericacea, the St. John’s wort family. This family is notable for having flower with very numerous stamens, making them look like little brushes. Both shrubs and herbs occur in the genus.

Shrubby St. John’s wort, Hypericum prolificum, with its opposite leaves, could be mistaken for a honeysuckle at first glance. The very most excellent Illinois Wildflowers web site explains that the flowers are visited by pollen-seeking bumblebees, syrphid flies and halictid bees. Sometimes, they tell us, butterflies and wasps land on the flowers seeking nectar, but to the disappointment of these lepidopterans, as the flowers offer only pollen as a floral reward.

Shrubbu St. John’s wort

Hypericum prolificum

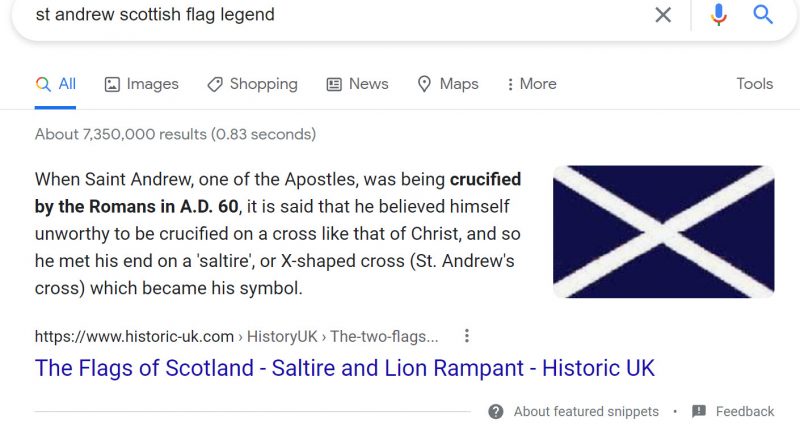

Here’s another St. John’s wort. This one is called “St. Andrew’s cross,” common-named for the peculiarly diagonal shape of the crucifix-like arrangement of the 4 petals. The specific epithet “hpericoides” means “looking like Hypericum,” so this is basically “Hypericum that looks like a Hypericum.” The epithet made sense once, when it was placed in a different genus, and known as Ascyrum hypericoides. When a species is transferred to a different genus, it usually retains its old specific epithet.

St. Andrew’s cross

Hypericum hypericoides

It shows up in the flag of Scotland. Here’s a short version of the story, told in screen capture, from this Scottish History web site.

St. Andrew’s cross explained.

My role in the bio-blitz was primarily to census bryophytes and lichens. For that, the most interesting area was a Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana) stand at the north end of the meadow. There are several lichens that specialize on pine branches, two of which are light gray narrow lobed foliose “starburst” lichens in the genus Imshaugia. These constitute an interesting sexually/asexually reproducing pair. Imshaugia aleurites is “salted starburst lichen,” so-named because it is covered with conspicuous prickly isidia. These are minute fingerlike projections consisting of upper cortex, algal cells, and fungal medullary hyphae that, collectively, comprise a “starter set” for a new lichen somewhere. This lichen was fairly uncommon at the site.

Salted starburst lichen

Imshaugia aleurites

Isidia city!

The American starburst lichen, Imshaugia placorodia, resplendent with tan-faced apothecia, was the most abundant lichen on these pine trees.

American starburst lichen

Imshaugia placorodia

Apothecium city!

In the evening some of the bio-blitzers set up a mothing apparatus. It was a big sheet stretched between two poles, and a super bright light.

One of the critters that flew to it is this lead-colored lichen moth, Cisthene plumbea. Its larvae feed on lichens!

Lead-colored lichen moth

This lichen is a treat to see, not only because it is uncommon, but because it was discovered by and named after an Ohio lichenologist friend, Ray Showman. This is Hypotrachyna showmanii, one of the so-called “loop lichens.” It is a light gray narrow-lobed foliose lichen that produces granular soredia. Usually found on chestnut oak, this one was on pine.

Ray’s loop lichen

Hypotrachyna showmanii