FIELD TRIPS

(actually from a couple years ago)

Cedar Bog that isn’t a bog.

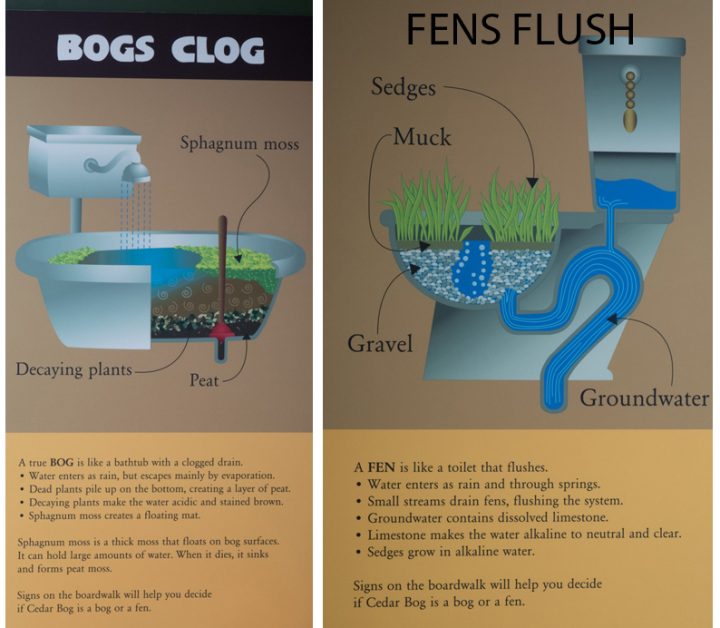

Before entering the bog that isn’t a bog we were given an introductory presentation by the director there, Mike Krackel, who explained the difference between a bog and a fen, and why Cedar Bog is actually Cedar Fen! Bogs clog and fens flush…which is to say that fens are fed from underground springs that percolate up through the sediment which is rich in calcium minerals that become dissolved in the water.

Bogs clog. Fens flush.

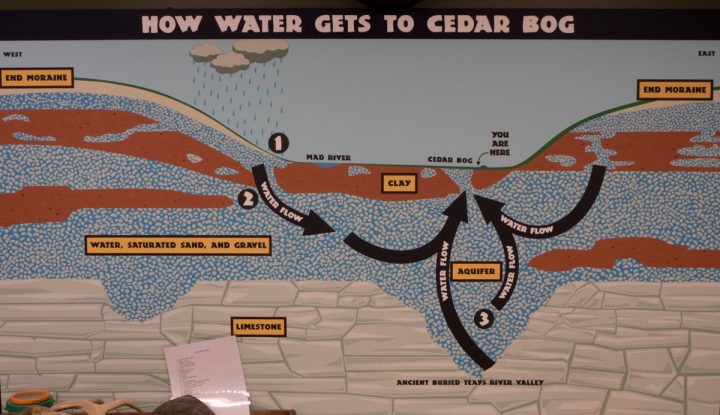

The spring were formed when glacial-transported gravel filled the valley of an ancient river system, the Teays (proniunced taze) River. The water is cool, which effectively shortens the growing season. Mike explained that Cedar Bog (which isn’t a bog) is unique in that plants from three different phytogeographic affinities are found in this one spot: northern bog plants, prairie plants and mid-western fen plants.

How water gets to Cedar Bog that isn’t a bog.

It’s a fen –a cool alkaline wetland fed by water up-welling through limestone sedimentary rock just below the surface. Many unique plants grow here. Since the nutrient levels are quite low, and the growing season short, some of them supplement their nutrient supply by digesting small animals. Carnivorous plants!!

Not very obviously carnivorous, obvious, unless you were to go pulling them out of the bog that isn’t a bog (It’s a fen!) are the bladderworts. These have leaves that are underwater, much divided, and some of the leaflets are modified into little pitchers that suck in tiny invertebrates that inadvertently touch trigger hairs in these bladders. The flowers are normal-looking, resembling yellow snapdragons.

Bladderwort (genus Utricularia) is a carnivorous plant.

During this tip we were introduced to the “coefficient of conservatism” from the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency’s Floristic Quality Assessment Inventory. In survey reports we use the coefficients of conservatism (CC) assigned to each species by Andreas et al. (2002). The CC, with values ranging from 0 to 10, is an estimate of the degree to which a species is associated with high-quality natural communities similar to those which existed in pre-settlement times.

We saw some very conservative species at this unique natural area. Here are three that received the highest score possible: a 10! (Note: that exclamation point is a grammatical mark meant to convey enthusiasm, not a mathematical “factorial” sign. As cool as green cotton grass, swamp birch, and marsh arrow-grass are, they don’t have CC values quite THAT high!)

Green cotton -grass, Eriophorum viridicarinatum (family Cyperaceae) is a sedge, bot a grass. The genus is distinguished by having hairlike bristles surrounding the tiny wind-pollinated flowers.

Green cotton-grass is a sedge.

Swamp birch, Betula pumila (family Betulaceae) is a shrub with a boreal distribution across North America found in calcareous wetlands.

Swamp birch is a northern shrub.

March arrow-grass, Triglochim palustre (family Juncaginaceae) is an inconspicuous monocot with basal linear leaves (not shown).

March arrow-grass is a rare fen monocot.

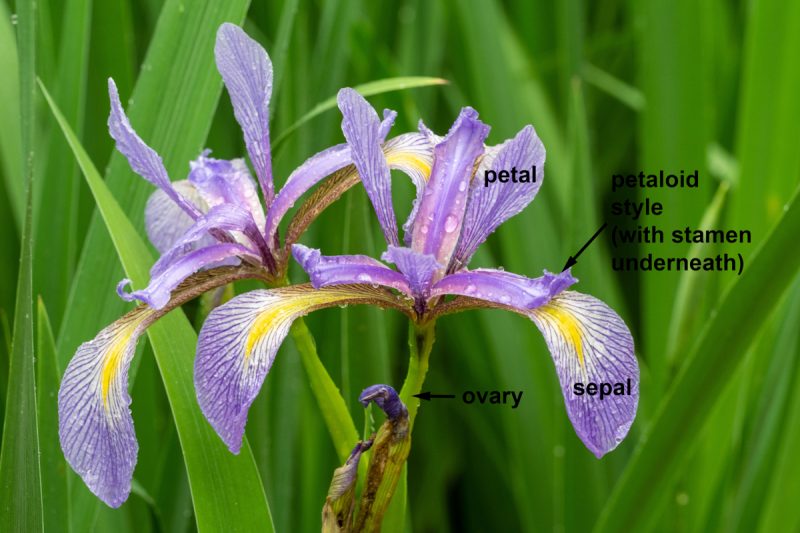

In addition to those very conservative rarities, it was a pleasure to see a more widespread wildfower, southern blue flag Iris, Iris virginica (family Iridaceae), a very showy monocot. Iris flowers are amazing! The ovary is inferior, looking in flowering specimens merely like an especially thick pedicel. As explained so well on this USDA website (link), both the sepals and petals are colorful and expanded, with the sepals substantially larger. They serve as landing platforms for bumblebees. The styles ate also petaloid, and are help clasped over the sepals, concealing a stamen (not shown in the photo below). The bee first encounters the stigmatic surface over her back, whereupon the stigma receives pollen from her. Immediately afterwards her body touches the stamen, thereby picking up pollen.

The iris flower sepals form a landing platform for bumblebees.

II. “Deep Woods” Preserve

Hocking County

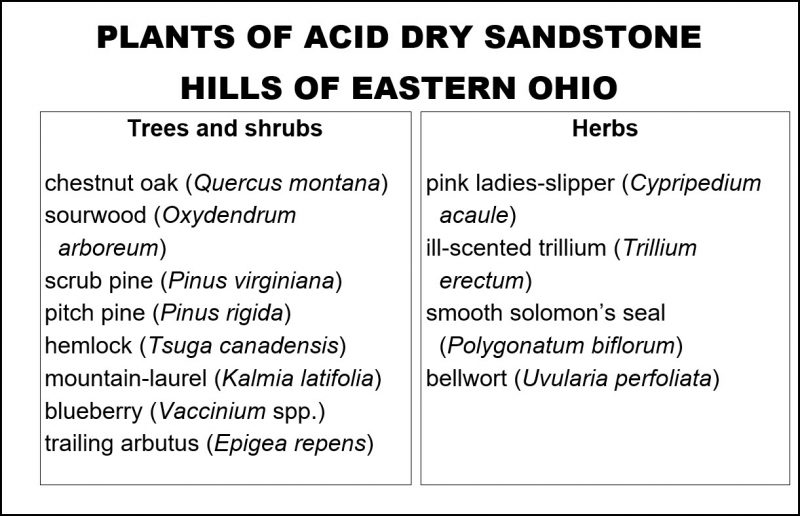

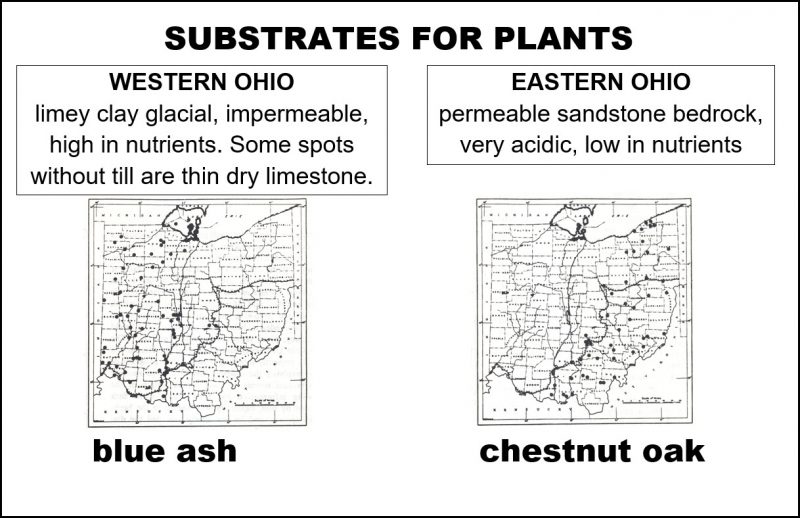

We visited Deep Woods, a private nature preserve in Hocking County. This 282 acre parcel has a rich variety of habitats representing many natural communities typical of the Hocking Hills region. Of particular interest to us was the presence of plants with a fidelity to acidic low-nutrient sandstone substrates, and to compare such indicator species here with others characteristic of calcareous conditions that we saw last week at Batelle Darby Creek Metro Park in Franklin County.

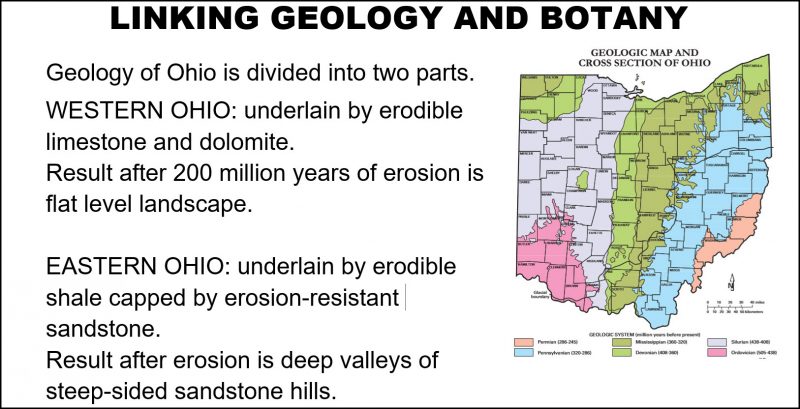

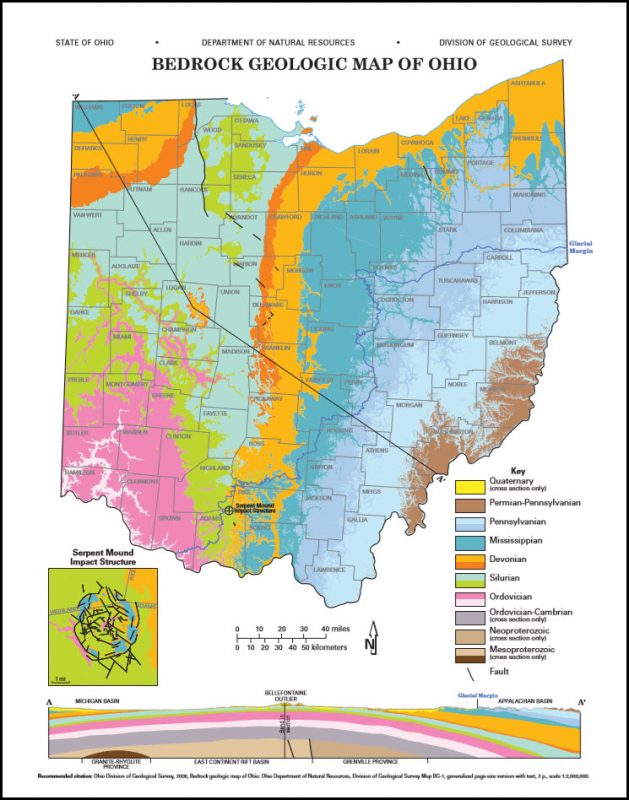

Our inspiration for this geologically informed viewpoint was Jane Forsyth’s 1973 article “Geobotany: Linking Geology and Botany.” In this article, Dr. Forsyth explains that the geology of Ohio (if not regarded too closely) may be divided neatly into two parts.

The reason for the difference in kinds of rocks is not difficult to understand. The original horizontal sequence of Sandstone atop Shale overlying Limestone was tilted into a shallow arch by pressure 200 million years ago, at the end of the Paleozoic Era. This exposed oldest rocks along N-S line in the west, at the crest of the arch. Erosion cut where the arch stood highest, exposing older rocks –limestones –in the west. Below, see an ODNR map, Bedrock Geologic Map of Ohio.”

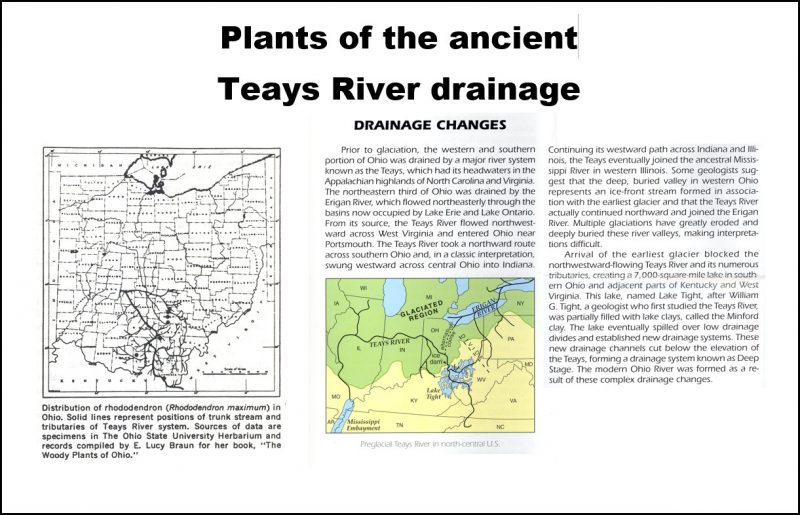

Prior to glaciation, much of Ohio was drained by the Teays River system, which originated in the Appalachian highlands. It flowed northwest across Ohio, then continued westward until joining the ancestral Mississippi River. Glaciers blocked this river, and, after the retreat of the glaciers, the modern Ohio River drainage was established. Some plant species, such as great rhododendron, have a distribution that is limited to the corridor of the ancient Teays River, leading scientists to postulate either that the plants are relics of that time, re-established from refugia where they occurred during glaciation in warmer areas south of the glacial boundary.

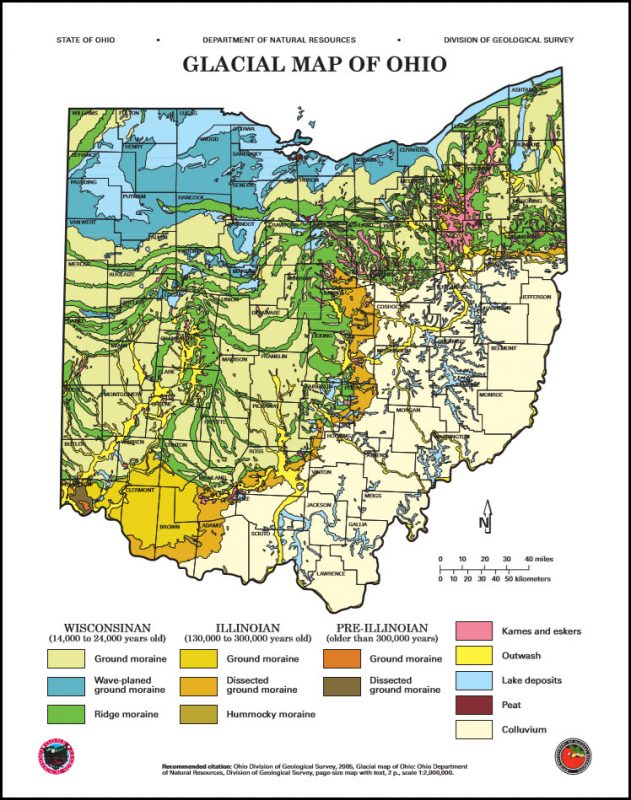

Pleistocene glaciers invaded OH a few hundred thousand years ago or less. Steep-sided sandstone hills in the east slowed the glaciers and caused there to be a glacial boundary cutting across. The glacial boundary can be seen in the ODNR maps below.

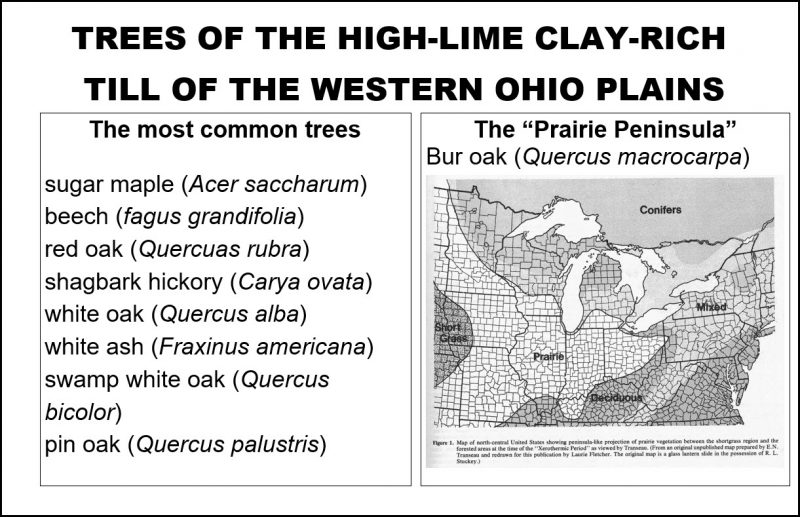

Glacial till was deposited by deposition by glaciers. Till is an unsorted mix of sand & gravel from meltwater. Till forms a blanket over most of glaciated OH, along with some local sand & gravel deposits.

Here at Deep Woods we saw chestnut oak (Quercus montana), a tree with a distribution strongly associated with acidic low-nutrient soils.

chestnut oak seedling

Some plants that would be scarce or absent entirely from Deep Woods that we saw at Batelle Darby Metro Park are redbud (which actually does occur in the Hocking Hills), redcedar, fragrant sumac, hackberry, and chinquapin oak.

Others are more broadly distributed across the till plains of western Ohio, namely sugar maple, beech, red oak, and white ash. These species occur in eastern Ohio as well, except they are not as predominant as they are in the western half of the state.

Along with the chestnut oak, we were pleased to see other woody species tightly associated with acid dry sandstone, namely sourwood, eastern hemlock, and blueberry.

Deerberry, Vaccinium staminium, an acid-loving member of the heath family.

An herb of acid sites, and one of our most spectacular wildflower, pink lady’s-slipper is an orchid.

Pink lady’s-slipper orchid, Cypripedium acaule, is associated with acid soils.

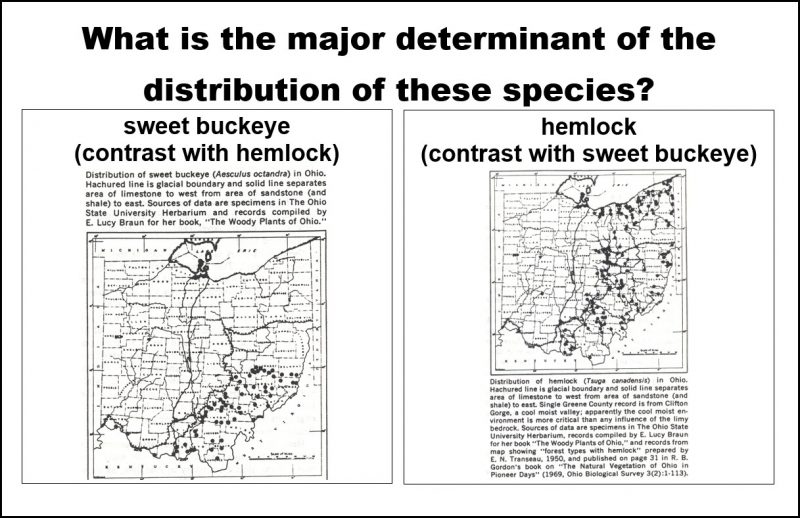

The glacial boundary sharply demarcates some plants’ distributions. For example, sweet buckeye (Aesculus octandra) a different species than the more familiar Ohio buckeye (A. glabra) only occurs south of the glacial boundary. By contrast, eastern hemlock occurs in cool sandstone ravines on both sides of the boundary in northeastern Ohio, showing that the cool moist environment is the key feature for this species.

I. Batelle Darby Metro Park

Battelle Darby Metro Park. In preparation for the Darby field trip, I visited the site a day ahead of time and also the day after because i forgot my camera(s) on field trip day. That was almost as much fun as it was going there with the class! (Almost.)

On a dry bluff overlooking Big Darby Creek, the soil is barren, and so is an ideal site for plants that are hemiparasitic, acquiring some of their nutrition through at attachment to the roots of other plants. Of special interest are plants with unusual modes of nutrition. Bastard toadflax (more respectfully called “false” toadflax), Commandra umbellata in the family Santalaceae is a hemi-parasite –a plant that derives some of its food from photosynthesis and some by being a root parasite in neighboring vegetation. I find that surprising because the plants are leafy and green, not looking at all different from “regular” plants.

False or bastard toadflax is a hemiparasite in the Santalaceae.

One plant that is clearly a parasite, being pale and leafless, is one-flowered cander-root, Orobanche uniflora (family Orobanchaceae).

One-flowered cancer-root is a wholly parasitic plant.

Nearby, an orchid was in flower. Orchid nutrition ranges from being parasitic to wholly autotrophic, as is this lily-leaved twayblade, L:iparis liliifolia. Nonetheless, all orchids (as far as I know) have strict obligate root-fungus associations. The twayblade was just beginning to flower.

Lily-leaved twayblade is an orchid.

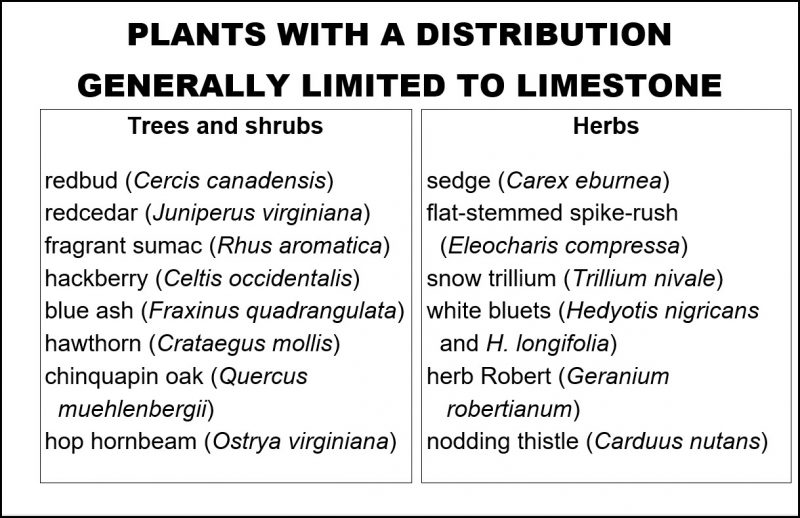

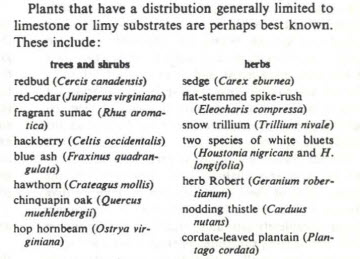

Batelle Darby Metro Park is located in an area of Ohio that was glaciated and the bedrock is calcareous (alkaline). As was pointed out by Jane Forstyth in the article “Linking Botany and Geology –a New Approach (The Explorer 1971), a suite of woody plants has been noted to occur in such sites, shown on the table below.

Plants of limestone areas, from the Jane Forsyth “Geobotany” article

Nearly all of the trees and shrubs listed were observed at the park: redbud, red-cedar, fragrant sumac, hackberry, and chinquapin oak. Here’s an example, Chinquapin oak.

Quercus muehlenbergii, Chinquapin oak, is especially common in limestone areas.